I delivered the following sermon at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Teaneck, N.J., on Trinity Sunday (June 11, 2017) for the 2017 graduation ceremony from the Education for Ministry program, a four-year distance learning seminar on bible literacy, church history and theology for which I am co-mentor.

Through the written word and the spoken word, may we come to know Your living word. Amen.

I had that dream again recently, the one where you realize the end of the semester is coming and there’s a class you haven’t attended since the first week. You’re not even sure where it meets or what you did with the book, but there you are trying to find the classroom, late, hoping to beg the professor for mercy.

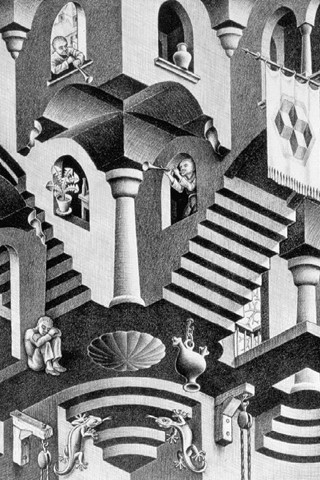

Psychologists, at least the ones on Google, say this dream is common and can represent latent anxiety about seemingly unrelated concerns. Some people who experience it report being in their pajamas or even naked, or wandering hallways that change before their eyes like an M.C. Escher drawing. In my particular version, there’s the added wrinkle of a dorm room that I paid for but haven’t been using, and on this fateful day I discovered my roommate had left it a disaster for which I was being held responsible. I woke up uneasy and confused, and trying to remember if any of it really happened.

I haven’t been a formal student in over five years so I have no idea what may have triggered it to recur. However, I told Margaret, one of three graduates from the Education for Ministry program whom we honor today, that if she finds a multiple-choice quiz on the Council of Nicea in her service leaflet today, she’s not dreaming and this is not a drill.

For the uninitiated, Education for Ministry (or EfM) is a four-year distance learning program to help adults explore their faith. It was born at and is managed by the University of the South, an Episcopal college and seminary in Sewanee, Tennessee. EfM graduates are typically not ordained, but the program reinforces the fact that all of us, clergy and laity alike, are called to engage in ministry, and their studies help them better recognize and employ their gifts to the glory of God and in service of others.

Today, as at every Sunday Eucharist, we heard readings from the gamut of scripture, beginning in the beginning, with the first of two stories of human creation in the Book of Genesis. This poetic account of how the world began does not, of course, reconcile with the things we are taught in science class. I assume most if not all of us have long accepted that the value of these ancient stories lies not in their provability, but in the narrative--as old as time--of a people and their God, who wrestle literally and figuratively with one another, break each other’s hearts, and find forgiveness.

This is all well and good when the stories are about talking serpents and burning bushes and people who live 700 years, but what happens when we get to Jesus? I think our culture has grown comfortable treating the “red letter” quotes in the Gospels as things he said verbatim, but one of the first things our second-year students learn is that the earliest of the Gospels was likely written at least sixty years after the events described. In our instant-replay world, our most direct experience of Jesus is subject to two generations of memory and interpretation. Additionally, in the Gospels as in the Hebrew scripture there are events--the resurrection and ascension being the most obvious among many--which just do not jive with what we observe and understand about the world around us.

The more you study, the louder this dissonance becomes. In our third-year text, Diarmaid MacCollough’s Christianity, the First 3,000 Years (which could be nicknamed 3,000 Years of Christians Behaving Badly) the historic and political origins of many of the doctrines most rank-and-file Christians take for granted are explored in depth. Some major decisions we might assume were made by the early disciples are in fact a lot more recent and seem to have been driven by political or practical concerns rather than the will of God. There are frequent occasions, right into our present century, when the institutional church hardly comes across as a hero. I re-read much of that book this year and it may well explain my anxious-exam dream. To quote Aristotle, Einstein or the British pop band UB40, depending on whom you ask, “The more I learn, the less I know.”

The more you study, the louder this dissonance becomes. In our third-year text, Diarmaid MacCollough’s Christianity, the First 3,000 Years (which could be nicknamed 3,000 Years of Christians Behaving Badly) the historic and political origins of many of the doctrines most rank-and-file Christians take for granted are explored in depth. Some major decisions we might assume were made by the early disciples are in fact a lot more recent and seem to have been driven by political or practical concerns rather than the will of God. There are frequent occasions, right into our present century, when the institutional church hardly comes across as a hero. I re-read much of that book this year and it may well explain my anxious-exam dream. To quote Aristotle, Einstein or the British pop band UB40, depending on whom you ask, “The more I learn, the less I know.” What, then, does it mean when we say we believe? Are we forced to choose between donning intellectual blinders when we recite the creeds, or simply picking and choosing what we want to accept?

The Rev. Dr. Peter Savastano, who teaches religion and anthropology at Seton Hall, said in a sermon recently:

“In my own quest to understand the historical Jesus, the Bible, and the Jesus of theology, the scholars I have read repeatedly point out that we twenty-first century humans have lost the art of reading and interpreting scripture symbolically and allegorically. Influenced by scientism and rationalism, we prefer instead to read and interpret scripture as though it is a scientific text or a technical manual.In other words, in our endless quest for data, we run the risk of turning off our brains’ ability to find value in that which cannot be proven. Is it still possible to not know in the temporal understanding of that word, but nonetheless believe?

Conversely, in the world of the ancients and in the medieval world, scripture was interpreted allegorically and metaphorically, drawing on our human capacity for symbolic thinking, our intuitive faculties, and by the use of our creative imagination. To interpret a sacred story or a myth allegorically—and from an anthropological perspective the Bible is both —is to read and plumb its depths for truths and lessons that have universal import, truths that can only be revealed over time by the slow and painstaking process of meditation, prayer, and contemplation.

All of this lack of concrete historical evidence should not make our God a stranger to us. The God we experience in our lives--in the community of the church, in our compassion for one another, or in the beauty of creation--is everywhere, known as intimately to us as our own internal organs, and the love of that God is--as Anglican historian and Dean for Religious Studies at Stanford University, the Very Rev. Dr. Jane Shaw puts it--the “glue” of our relationships to one another. Although EfM is not therapy, we have seen real evidence of that glue as we supported one another through the changes and chances of life. In a recent reflection, Peter Grace, who graduated from the program in San Francisco in 2014, wrote “For us Christians, God is anything but unknowable: is not outside of us, but truly alive at the very center of our being and ‘does not live in shrines made by human hands.’ God is not a question to be answered, but a mystery to be embraced.”

Speaking of mysteries, today we focus on the Holy Trinity, the true nature of which theologians have been arguing about for almost as long as Christianity has been a thing. But this too need not and should not be limited to some arcane, eye-crossing concept that we blindly accept or mostly ignore. We are charged with using our gifts of memory, reason, and skill to explore what wise women and men of faith continue to say about this and how we can interpret it in our own lives. For example, the modern Franciscan Catholic theologian and author, Fr. Richard Rohr asserts, “In the beginning was the Relationship.” and goes on to simply and elegantly describe the three entities of the Trinity as “the God who made the world and everything in it,” “Jesus Christ, who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God” and “the spirit of truth...who abides with you and will be in you.”

The EfM journey may at times awaken cynicism, disenfranchisement, and uncertainty, but we would hardly be the first to wrestle with that. As we heard in today’s Gospel, even the disciples who saw Jesus in person experienced doubt. But there is great joy and comfort in exploring them together, and newfound ownership of a faith which one has examined carefully from many sides in an environment where such questions are not just welcomed, but expected.

Barbara, Margaret and Terry, it is the prayer of your EfM family that you proceed to the next chapter in your ministry equipped with clear-eyed wisdom about your faith and its often flawed but nonetheless inspiring history, having read the scriptures alongside expert--if sometimes slightly arid--context. You studied and practiced how to make the theological become personal; prayed, laughed, and sometimes wept with us.

We commission you today to use all these insights and experiences to build and strengthen the gifts you bring to a changing church and hurting world, to be--in the words of Teresa of Avila--the hands, the feet, the very body of Christ.

Finally, my sisters, farewell, but not goodbye. Your classmates and fellow alumni will be near at hand to continue supporting your walk of faith and service. We pray that the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of* the Holy Spirit be with you always, even to the end of the age. Amen.

I enjoyed reading this sermon (and look forward to your preaching at Christ Church on the 25th!). Thank you for sharing it.

ReplyDeleteWhat a powerful and beautiful sermon. I am both honored and flattered to be quoted in it and like very much the innovative direction in which you developed it.

ReplyDelete