One from the archives... this sermon was given at Evening Prayer on Independence Day 2004. Startling how little has changed in 13 years.

There’s nothing like a good famine to put things in perspective.

On

Tuesday, Andrew Natsios, the head of the U.S. Agency for International

Aid, said matter-of-factly of the humanitarian crisis in the Darfur

region of Sudan, "If nothing changes we will have one million

casualties. If things improve we can get it down to about 300,000

deaths.” 1.2 million black Africans have been driven from their homes

by years of fighting, and are living on the run, constantly menaced by

hunger, disease, and the marauding Arab militias that roam the country

unchecked, and sometimes encouraged, by the Sudanese government.

Meanwhile,

halfway around the world, Christians in the richest country in the

world, where the food wasted in one day could probably save those

million people, have other things on their minds.

At the most

recent General Conference of the United Methodist Church (equivalent to

our General Convention), homosexuality was determined to be the top

issue facing the church, taking priority over war and violence, poverty,

racism, and that denomination’s double-digit decline in membership.

Catholic

priests and bishops around the country are not only refusing Communion

to politicians whose positions are not in step with that of the Vatican,

but discouraging those who vote for them from receiving it as well.

Ronald

Reagan was praised by his son for not wearing his religion on his

sleeve, in a none-to-subtle jab at how fashionable it has become among

politicians to do just that. The “WWJD” crowd wears Jesus like a logo,

many with little understanding of who He was or what He stood – and died

-- for.

And within our own Episcopal family, people are leaving

churches they and their families have attended for generations, because

they choose to narrowly interpret some seven verses of Scripture while

ignoring dozens of others, and refuse to break bread with anyone who

doesn’t share their interpretation.

What makes this all the

more frustrating for me is knowing that I’m just as guilty of getting

caught up in the partisan bickering as anybody else. Last week, I heard

that 36 members of a parish in New Hampshire left because they don’t

accept the authority of Bishop Gene Robinson, leaving just three people

to keep the parish going. The following Sunday, when I heard there were

nearly a hundred people in the church, the small wave of glee I

experienced was not exactly charitable.

.

It’s a small wonder

that a common mantra of the un-churched is “Sure I love Jesus, it’s His

followers I can’t stand!” None of this dirty laundry escapes the

drama-hungry press, and outsiders must scratch their heads and wonder

which liturgical season it is when we take a break from finger-pointing

and actually pray.

Today’s lessons neatly summarize what it is

God expects from us. In Deuteronomy, “You shall … love the stranger,

for you were strangers.” And in the Gospel reading, we are told “Love

your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be

children of your Father in Heaven; for He makes the sun rise on the evil

and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous”

In

other words, none among us is equipped to decide who is deserving of

God’s love, or who deserves to be in God’s house. God is capable of

figuring that out without our help, and the time we use to judge one

another takes us away from the task with which we were entrusted.

Christ made it clear that God’s love is universal, and demonstrated that

by always surrounding himself by the marginalized, unpopular,

“hard-to-love” types who cause us to get self-righteous or crack jokes

or divert our path. Christ asked us to be His hands, He expects us to

get those hands dirty, and give those people who take us outside our

comfort zone the same dignity that He would. If we concentrated on

that, we’d be far too busy to notice one another’s imperfections.

In

the reading from Hebrews, Paul talks about Abraham and Sarah and their

kin, who had little more than their faith to sustain them when they

lived in tents in a foreign country, waiting for God’s promises to be

fulfilled. Fast-forward to 2004, and Abrahams and Sarah’s are all

around us, as many as the stars of heaven, in refugee camps and homeless

shelters, in detention centers and on street corners, barely daring to

dream of a heavenly city of their own design. It’s easier for us to

insulate ourselves in our own cares, blame others for the world’s

problems and pretend they’re not our responsibility, but if we each

tried just that little bit harder to get past the rhetoric and focus on

WWJ really D, then – brick by brick -- that city would be reality,

instead of something millions of people die dreaming about.

Wednesday, July 12, 2017

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

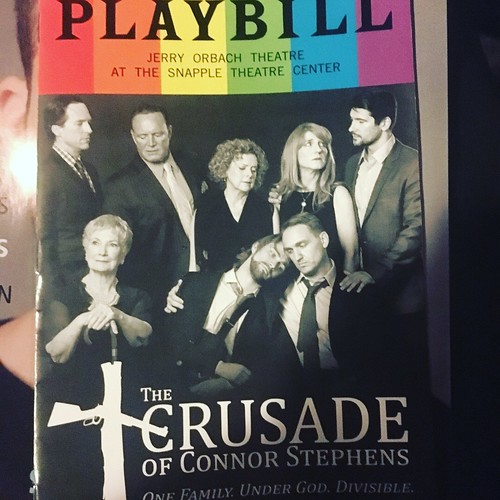

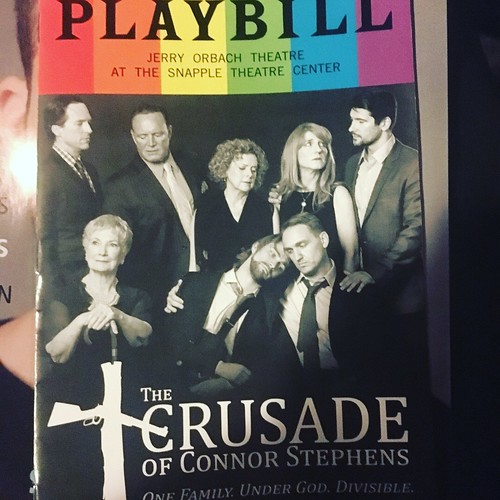

God, Gays & Guns, Redux: Connor Stephens Arrives Off-Broadway

Cornelius Hill - Priest & Chief Among the Oneida (1907)

Playbill for The Crusade of Connor Stephens.

Top row, from left, Clifton Samuels (Dean), James Kiberd (Big Jim), Katherine Leask (Marianne), Julie Campbell (Kimmy), Jacques Mitchell (Bobby). Front row, from left, Kathleen Huber (Viv'in), Alec Shaw (Kris), Ben Curtis (Jim, Jr.).

The Fantasticks this is not. A makeshift memorial as you enter the theater sets the tone for this gripping and cathartic play.

Writer-Producer Dewey Moss hugs James Kiberd (Big Jim) during the curtain call on opening night of The Crusade of Connor Stephens. From left, Jacques Mitchell (Bobby), Julie Campbell (Kimmy), Ben Curtis (Jim, Jr.), Alec Shaw (Kris). At right, Katherine Leask (Marianne), Clifton Samuels (Dean).

“Oh, Jesus, I have to stop you right now. I love you dearly: You're a smart and sweet man, but you are so wrong about what matters and where the eyes should visit. The things you find so important--the attention, the prizes, the approval--yes, they matter, and never so much than when they disappear. But I'm old now, and I've walked a long and rocky road, and what really mattered, what should matter most to you, is the rare and gorgeous experience of reaching out through your work and your actions and connecting to others. A message in the bottle thrown toward another frightened, loveless queer; a confused mother; a recently dejected man who can't see his way home. We get people home; we let them know that we're here for them. This is what art can do. Art should be the arm and the shoulder and the kind eyes--all of which let others know you deserve to live and to be loved. That is what matters, baby. Bringing people home.”

- TENNESSEE WILLIAMS

Last night we had the privilege of attending the opening night of The Crusade of Connor Stephens at its new off-Broadway home in the Jerry Orbach Theater, once-home of the record-breaking The Fantasticks. You may recall that I reviewed this show when it was included in the Midtown International Theatre Festival last summer, so I won't tell you the whole plot again. Sufficient to say, it felt even more timely the second time around here in the Drumpfpocalypse, post Pulse Nightclub massacre, when mass shootings are a near-daily occurrence and demonizing one another with half-truths is what subsists for news.

Almost the entire cast* returned for this new production, which says something about their commitment to this important story and their devotion to writer-producer Dewey Moss. At this point I could not in good faith accept a paid gig to write something unbiased about the show because in the year since I have gotten to know Dewey and Jacques Mitchell (Bobby) and consider them friends. However I will still say the show was just as gripping and cathartic the second time around, especially for anyone who has been church-burned or lived under the thumb of a controlling narcissist (well that would be the whole country at the moment, would it not?) as so skillfully portrayed by James Kiberd (Big Jim).

I did, however, write a brief interview of Ben Curtis (Jim, Junior) which appeared in the June edition of the Episcopal Journal. We discovered when we met in 2015 that we're both "PK's" (preacher's kids); my dad being a Roman Catholic deacon and his a now-retired Episcopal priest. I thought that would make an interesting angle for a story, given the contrast between his fundamentalist on-stage father and his real-life dad's progressive stance. The text of my interview is below:

God, gays, and guns collide in The Crusade of Connor Stephens, a play written and produced by Dewey Moss which

has its off-Broadway premiere later this month after an award-winning

workshop run last summer. I caught up with former Dell computer pitchman

Ben Curtis,

who will reprise his role as Jim, Jr., a gay man whose adopted

daughter's death puts him at odds with his firebrand minister father

"Big Jim" and thrusts the family into the media spotlight. Ben hails

from Chattanooga, Tenn, where his father was Rector of Grace Church from

1979-1994. Besides acting, he operates a yoga and wellness practice

with his fiancee and performs in a variety of musical groups.

Q.

I was proud to hear you identify as an Episcopalian in your recent

interview with ESPN. Given your work helping others with their own

health and spiritual journeys, how does the church fit into who you are

and what you believe?

Well

it certainly formed some of my earliest beliefs as a Christian and my

roots in spirituality. The church provided education, structure and

community that I needed as a young wild rebellious PK (preacher's kid).

It also helped me develop my early ideas of faith. Our parish and the

Episcopal Church in general is so open-minded and accepting of all

people, so that really instilled my core feelings as a child that all

people are equal and all are loved by God. I still believe that today,

and my father, while he was the rector of our parish, walked the walk.

Q. Like your character, you grew up as a "preacher's kid". How did that experience help you portray Jim, Jr.?

Well,

it certainly helped me understand the pressures of being in the

spotlight of the church. I was a satisfied customer of the Episcopal

Church, so I was involved as an acolyte or in the choir. Nevertheless,

if I made a mistake or got in trouble, you can be certain that everyone

knew about it.

However, unlike Jim, Jr., my father did not force me to think one way

nor tell me that I was going to hell if I thought a different way.

Q. The Episcopal Church has been vocal about LGBT justice, as well as gun violence, both themes which the play explores. How did being an Episcopalian help shape how you see these issues?

I

feel blessed to have grown up in a church very different from the one

that Jim, Jr., did, which sounds very oppressive. I have friends who

grew up in churches like that and who were put in conversion therapy,

which of course is never effective.

I

am very grateful to have grown up in such an accepting environment that

allowed me to form my own ideas of God and spirituality. I feel sorry

for people who are told by their church or pastor that being a Christian

is black and white: “you're either saved or you ain't.” I believe our

God is a loving God and Jesus was a great prophet. We can learn a lot

from his stories and how he treated other people, ESPECIALLY the

outcasts or those “different” from him.

Q. How do you relate believably to an on-stage "family" whose values contrast so starkly with your character's?

It's

not hard. I don't believe in their “Christian morals” as a person so

it's fairly easy to be disgusted by them on stage. Furthermore, they're

brilliant actors, so the tension on stage is quite palpable. That and

when your stakes and intentions are clear as an actor, the rest tends to

work itself out.

Q. If Dewey told you that you had to play Big Jim tomorrow, could you do it? What would you do to get into that character?

Absolutely! I've played lots of “complicated” and “awful” characters. Each character wants something. If you know what yours wants, then that's your job on stage: to listen and to get what you want, or at least try. This script is also well-crafted so the words guide you. No matter what kind of character I play, I always find and play the truth and the humanity. Even Big Jim is quite human.

Absolutely! I've played lots of “complicated” and “awful” characters. Each character wants something. If you know what yours wants, then that's your job on stage: to listen and to get what you want, or at least try. This script is also well-crafted so the words guide you. No matter what kind of character I play, I always find and play the truth and the humanity. Even Big Jim is quite human.

Top row, from left, Clifton Samuels (Dean), James Kiberd (Big Jim), Katherine Leask (Marianne), Julie Campbell (Kimmy), Jacques Mitchell (Bobby). Front row, from left, Kathleen Huber (Viv'in), Alec Shaw (Kris), Ben Curtis (Jim, Jr.).

The man of the hour. Writer-producer Dewey Moss beams as the audience shows some love.

From left, Jacques Mitchell (Bobby), Julie Campbell (Kimmy), Ben Curtis (Jim, Jr.), Alec Shaw (Kris). At right, James Kiberd (Big Jim), Katherine Leask (Marianne), Clifton Samuels (Dean).

Ben Curtis (Jim, Jr.) and yours truly on the red carpet.

NOTE: James Padric, who portrayed Kris in the workshop run, was diagnosed with esophageal cancer shortly after the production. He is doing well but could still use your support in the face of hefty medical bills. Thank you!

Sunday, June 25, 2017

A Seat on the Bus: Sermon for Pride Sunday

3rd Sunday After Pentecost

Through the written word and the spoken word, may we come to know your living word. Amen.

I begin by offering my profound thanks to Mother Diana for the opportunity to reflect upon the word of God and the history of a movement with you today. She frequently refers to me as an “activist” which awakens some vague sense of guilt as I am not as active as I once was. From 2002 until 2014 I served with both The OASIS, our diocesan ministry to and with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, and Integrity, the churchwide LGBT advocacy group.

On the cover of your leaflet is a photo of the 2013 LGBT Pride March in New York. The march, which will take place later today, has been held on the last Sunday in June since 1969, commemorating the civil uprising that took place at the Stonewall Tavern that summer in response to years of systematic persecution of LGBT people by the police and mocking indifference from almost everybody else.

If you study the photo you’ll see familiar symbols: just about everybody you see is an Episcopalian or connected to the church in some way, and in fact the Episcopal Church is one of the largest single groups of participants in the March. On the banner in front and on the top of our float, barely visible a full city block away, are our church shield and the words “The Episcopal Church Welcomes You”.

That welcome was not and is not always something that could be counted on. In the summer of Stonewall, LGBT people in the church were pariahs like Hagar and her son in today’s first reading: they were perceived as a threat or dismissed as a joke, and not allowed to inherit the gift of community the church offered, unless they were willing to keep their relationships and very identity a secret. In 1974 a young English professor named Louie Crew… remember that name, if you don’t know it already… telephoned Grace Cathedral in San Francisco asking how he and his husband might meet other gay Episcopalians. The staff there laughingly passed his call around the office, making him repeat his question for their amusement. That encounter led him to start a network called Integrity which grew to be the de facto voice of LGBT people within the Episcopal Church.

There are many within the church, including within leadership, who believe with conviction that the six specific verses in scripture condemning same-gender behavior--what we in the movement call “The clobber passages”--take precedence over the broader themes of tolerance and justice found in the Gospels. As a result the process of claiming our place at the table is taking a long time and hard work by many people.

From 1976, issues of gender and sexuality have been the topic of conversation at all of the church’s triennial General Conventions, where clergy and laity from every diocese gather to steer the church forward. At that meeting, the church decided to begin ordaining women. The following year, an out lesbian, Ellen Barrett, was among the first women to be ordained as a priest. At the next convention, in 1979, the previous progress was overshadowed by a strong statement against such ordinations by the House of Bishops, drafted by Bishop Bennett Sims of Atlanta. Remember that name too.

Progress at the churchwide level continued in fits and starts. At his installation as Presiding Bishop in 1986, Edmund Browning proclaimed, perhaps prematurely, that “This church of ours is open to all. There will be no outcasts."

For many years, members of our own diocese, including members of this congregation if memory serves me, were among those marchers in New York. We drew international attention when we ordained the first partnered gay man, Barry Stopfel, in 1989. That move got Walter Righter, the retired bishop who ordained him, brought up on heresy charges by some of his peers which were not dropped until years later. Far from backing down, Righter proudly had HERETIC made up as his custom license plate.

Along with the Diocese of California--we in Newark were the first to have a specific ministry for lesbian and gay people, the OASIS, beginning in 1989. Special worship services were planned since people did not feel safe being out at church. Notice I did not say “LGBT” because inclusion of those groups has not evolved on the same timetable, and there are still many within the movement who do not feel we all belong under the same rainbow umbrella.

The tide of opinion really began to turn between the 1991 and 1994 conventions. During that time, some 30,000 Episcopalians in 1,100 congregations across the church participated in a parish dialogue about human sexuality which many said helped them to see gay and lesbian people--we’re still only at gay and lesbian, notice--as people rather than “an issue” As a result of this churchwide conversation, a “Statement of Koinonia” (fellowship) with gay and lesbian people drafted by our bishop at the time, John Shelby Spong, was signed by over 70 of his peers, including Bishop Sims, the same man who led the charge against ordination of openly gay and lesbian clergy! Sims said, “When I wrote that Pastoral Statement in 1977, I knew only one homosexual person up close. He scared me to death with his penetrating challenge that he was as complete a human being as I was.” He was talking about Louie Crew, the English professor who founded Integrity and later went on to serve on the Executive Council of the Episcopal Church. Today he lives not ten miles from this room and goes by Louie Clay, having taken the name of his husband Ernest of 40 years when they were legally married in 2013.

In 2003 the church made the news again when Gene Robinson, an out gay priest, was ordained the bishop of New Hampshire. He was not the first gay bishop: Otis Charles of Utah came out in 1993 while already seated, and Paul Moore of New York was posthumously outed by his daughter. But by choosing to consecrate him while already knowing that he is gay , the church again drew both criticism and praise from around the world.

As you probably know the Episcopal Church is part of a larger church, the Anglican Communion, which is somewhat symbolically overseen by the Archbishop of Canterbury in England. Some of the provinces of the church, notably Uganda and Nigeria, threatened to leave the communion as a result of Robinson’s consecration.

In response to this outcry, we in the Episcopal Church agreed somewhat reluctantly at the 2006 General Convention to "exercise restraint by not consenting to the consecration of any candidate to the episcopate whose manner of life presents a challenge to the wider church." Those of us who knew we presented the church with a challenge just by being in the room were strongly encouraged by Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts-Schori, and--in an unprecedented move--Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams to temporarily sacrifice ourselves in the name of unity. The Archbishop has no legislative authority outside the Church of England, but his presence and influence at that Convention was a sign of how close to coming apart he feared the Anglican Communion was.

However, we did not behave ourselves for long. In 2009, Mary Douglas Glasspool, an out lesbian, was ordained assistant bishop of Los Angeles. A significant number of congregations in the US and Canada then left their respective churches and created the Anglican Church in North America, an expression of conservative anglicanism which has not been formally recognized by the Communion. The foundations of the Episcopal church trembled again, but held.

Parishes and dioceses for many years performed home-grown rites for recognizing and blessing committed same-gender relationships, increasingly as civil marriage equality became the law of the land in more and more states beginning with Massachusetts in 2003. Finally, after numerous dioceses used a trial rite for blessing of a civil marriage for a number of years, General Convention in 2015 voted to make marriage equality available throughout the church, just days after the Supreme Court ruling, two years ago tomorrow, that brought marriage equality to every US state. There are still some dioceses and parishes which will not perform them but the practice has the official sanction of the church and in many congregations a wedding is a wedding, regardless of the genders of the couple..

That was a lot of information about the G and the L, now let’s talk briefly, I promise! about the B and the T, for bisexual and transgender. In 2012, the church finally began to recognize gender identity as another social justice issue that required prayerful work. The General Convention in that year resolved that being transgender was not in itself a barrier to ordination, and that the church must advocate for non-discrimination laws in the civil sector. In practice, transgender clergy have had a difficult time finding employment just as their sisters and brothers in the secular world struggle with job security. The poverty rate among the trans population is approximately four times that of the general populace.

Finally the B, where we have perhaps the most work to do. People who identify as bisexual make up the largest wedge of the LGBT pie, and yet are probably the least visible or understood. In 2014, a nonprofit organization called the Religious Institute published a workbook for people and congregations to begin increasing their literacy and creating welcome.

In the past ten years or so, a “Q” was sometimes added to LGBT, standing for queer. Once used mainly as an insult, the community has claimed and disarmed this word as an umbrella term for anyone whose combination of identity and attraction is not easily labeled. An increasing number of people, particularly young people, are resisting traditional norms and embracing a more fluid way of expressing themselves. If it wishes to remain relevant to them, the church needs to meet them where they are or at least hear their perspective.

In the meantime, all these lofty resolutions and decisions needed to be made real at home, in the parishes. In 2010, the Episcopal Church, by way of Integrity, joined 13 other denominations in the Believe Out Loud program which is intended to help congregations become more informed about issues of sexuality and gender and advocate more effectively for justice and equality.

Because LGBT inclusion came early to the Diocese of Newark, it has now somewhat faded from the forefront, and is perhaps even taken for granted by those who enjoy the benefits.,There were a few years when only a handful of us crossed the river to join the march, and response to the programs the OASIS offered has largely waned. This is not meant as an indictment of anyone. To some degree it means those early pioneers for justice succeeded in their work, and worthwhile issues like gun violence, the plight of the undocumented, refugees, hunger and housing insecurity all demand our attention as we seek to be Christ’s hands in a hurting world.

However, there is also overlap as race, culture and economic status bring a disparity in the degree to which our LGBT sisters and brothers enjoy welcome, safety and opportunity both in the church and the world. Paradoxically for those Christians who believe our faith calls us to seek justice for all God’s children, cultures which are heavily religious are often slower to offer acceptance.

Like the dire family apocalypse Jesus predicted in today’s gospel, some LGBT people find themselves abandoned or even betrayed by family and community when they need them most. Recently in Chechnya, over 100 gay men were recently rounded up by police, many turned in by relatives, and subjected to verbal and physical abuse. Around the world the disproportionate number of transgender women of color who die violently every year, their attackers rarely caught.

And right here at home, five of the 49 people who died in the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando last year were buried at the city’s expense, because their families, some of whom did not know the victims’ orientation or gender identity prior the attack, could not or would not plan their funerals. One father would not even claim his son’s body.

State legislatures, perhaps in a backlash to the Supreme Court ruling on marriage equality in 2015, have tried to enact new laws limiting protections and freedoms based on orientation or gender identity and expression. In over 50% of the states, being LGBT can still get you fired from your job. Sadly for people of faith, In many of these cases lawmakers cite “religious freedom” as grounds to perpetuate this discrimination. We as a population are more likely to fall victim to substance abuse and suicide, and our seniors, often without their own offspring to advocate for them, sometimes end up going back in the closet just to feel safe in retirement or nursing homes.

I realize that is a gloomy summation of where things are, but it serves to remind us that not everyone has found the love and safety we believe all God’s children deserve. There is plenty for which we can find joy as well. As I described, our own church has made tremendous strides to embrace LGBT people, as have a number of other mainline denominations. And earlier this month, the new Archbishop of Newark met a delegation of LGBT Catholics at Sacred Heart Basilica. There is much work to be done, but at least there has been dialogue.

In the wider world, out LGBT people are found in places of leadership in politics, the arts, business, and even professional sports. Schools, including the Bloomfield and Glen Ridge public districts, have gay-straight alliances and have adopted policies to ensure the fair treatment of transgender students. Our governor signed the first law in the country preventing parents from forcing conversion therapy on their kids. We find ourselves and our lives depicted increasingly in the media, sometimes even by actual LGBT people!

Here at Christ Church, a home was created for P-FLAG, an organization for the parents of LGBT children. Familiar symbols including the Believe Out Loud branding signal to passersby that this is a place where they are safe, welcomed, and celebrated. I am pleased that Christ Church has chosen to identify as a Believe Out Loud Episcopal Congregation and hope we can continue to explore together what that means in this time and place.

As Paul tells us today, in baptism, we all die to sin, just as Christ--who had no sin--died to sin, once for all. In our own tradition, we pledge at baptism to seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving them as ourselves, and respecting the dignity of every human being. Each of us has our own struggles with that, I suspect, as we encounter people who challenge the way we’ve come to understand our world. Those of us who are LGBT know we can cause those feelings simply by being who we are, but that doesn’t stop us from having them about other people either. If we agree that sin is anything that separates us from God, I ask we all be aware of those times when we allow the prejudices we all carry to win out over that calling to love each other without condition.

Thankfully, in perhaps the greatest news in today’s lessons, we have the best possible teacher. No matter how we might excel at loving one another, current science cannot calculate how small a fraction that is of the reckless, shameless love our God has for each of us. Every hair on our heads is counted, the secrets our hearts are open and all our dreams known.

My prayer today, for all of us, is that we never stop learning about one another, hearing one another’s stories, wiping one another’s tears, sharing one another’s joy, and seeking to recognize each person we meet as the precious creation of God that they are. That we turn to one another and say, “I see you, heterosexual newlyweds, homeless gay man, bisexual woman, transgender artist, queer youth. I see you, widowed priest, Choctaw bishop, black attorney, wheelchair warrior. I see you, undocumented worker, frightened asylum seeker, grieving mother, struggling breadwinner. I see you, proud soldier, neglected veteran, dedicated policewoman, devoted teacher, autistic child. And when I see you, I see Jesus.”

Then, and only then, will the church become what Bishop Browning proclaimed we were and thus challenged us to become: a church where all are truly welcome as their authentic selves, and there are truly no outcasts.

Then and only then will our baptismal covenant be truly realized.

Then and only then will the cries of those on the margins due to their attractions or their appearance or their circumstances be heard like God heard Hagar and her son and find comfort and peace within our walls.

Then and only then will “pride” not be code for “solidarity” in a struggle that never seems to end.

Then and only then will we not have to remind people that our lives matter because it will be safe to assume that they know and agree.

Then and only then will our laws truly bring liberty and justice to all.

Then and only then will we reveal the face of Christ, no longer bloody but GLORIOUS, upon the earth.

This year the Pride March will be televised for the first time, but I will not be marching today. After over twelve years of work among leaders of the movement, many of whom were coping by varying degrees, with the battle scars of their own history, I experienced burnout and had to step aside and into the wilderness. But I have not given up. I frequently pass this forlorn-looking old double-decker bus on a used car lot in Belleville, and--perhaps as a sign I’m becoming one of those Crazy Christians that Presiding Bishop Michael Curry says we should be-- I never fail to spend the next few miles daydreaming how cool it would be to ride down Fifth Avenue on that bus, decked out with a huge banner saying the Episcopal Diocese of Newark welcomes you… just as you are”. In my dream we use it not just for Pride but for Memorial Day, Thanksgiving, Martin Luther King Day, or any time where the church needs to make a visible witness to the world.

I ask God’s blessing upon you, and upon your own dreams. And If I figure out a way to get that bus, I’m saving you a seat. Amen.

SOURCES:

Through the written word and the spoken word, may we come to know your living word. Amen.

I begin by offering my profound thanks to Mother Diana for the opportunity to reflect upon the word of God and the history of a movement with you today. She frequently refers to me as an “activist” which awakens some vague sense of guilt as I am not as active as I once was. From 2002 until 2014 I served with both The OASIS, our diocesan ministry to and with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, and Integrity, the churchwide LGBT advocacy group.

On the cover of your leaflet is a photo of the 2013 LGBT Pride March in New York. The march, which will take place later today, has been held on the last Sunday in June since 1969, commemorating the civil uprising that took place at the Stonewall Tavern that summer in response to years of systematic persecution of LGBT people by the police and mocking indifference from almost everybody else.

If you study the photo you’ll see familiar symbols: just about everybody you see is an Episcopalian or connected to the church in some way, and in fact the Episcopal Church is one of the largest single groups of participants in the March. On the banner in front and on the top of our float, barely visible a full city block away, are our church shield and the words “The Episcopal Church Welcomes You”.

That welcome was not and is not always something that could be counted on. In the summer of Stonewall, LGBT people in the church were pariahs like Hagar and her son in today’s first reading: they were perceived as a threat or dismissed as a joke, and not allowed to inherit the gift of community the church offered, unless they were willing to keep their relationships and very identity a secret. In 1974 a young English professor named Louie Crew… remember that name, if you don’t know it already… telephoned Grace Cathedral in San Francisco asking how he and his husband might meet other gay Episcopalians. The staff there laughingly passed his call around the office, making him repeat his question for their amusement. That encounter led him to start a network called Integrity which grew to be the de facto voice of LGBT people within the Episcopal Church.

There are many within the church, including within leadership, who believe with conviction that the six specific verses in scripture condemning same-gender behavior--what we in the movement call “The clobber passages”--take precedence over the broader themes of tolerance and justice found in the Gospels. As a result the process of claiming our place at the table is taking a long time and hard work by many people.

From 1976, issues of gender and sexuality have been the topic of conversation at all of the church’s triennial General Conventions, where clergy and laity from every diocese gather to steer the church forward. At that meeting, the church decided to begin ordaining women. The following year, an out lesbian, Ellen Barrett, was among the first women to be ordained as a priest. At the next convention, in 1979, the previous progress was overshadowed by a strong statement against such ordinations by the House of Bishops, drafted by Bishop Bennett Sims of Atlanta. Remember that name too.

Progress at the churchwide level continued in fits and starts. At his installation as Presiding Bishop in 1986, Edmund Browning proclaimed, perhaps prematurely, that “This church of ours is open to all. There will be no outcasts."

For many years, members of our own diocese, including members of this congregation if memory serves me, were among those marchers in New York. We drew international attention when we ordained the first partnered gay man, Barry Stopfel, in 1989. That move got Walter Righter, the retired bishop who ordained him, brought up on heresy charges by some of his peers which were not dropped until years later. Far from backing down, Righter proudly had HERETIC made up as his custom license plate.

Along with the Diocese of California--we in Newark were the first to have a specific ministry for lesbian and gay people, the OASIS, beginning in 1989. Special worship services were planned since people did not feel safe being out at church. Notice I did not say “LGBT” because inclusion of those groups has not evolved on the same timetable, and there are still many within the movement who do not feel we all belong under the same rainbow umbrella.

The tide of opinion really began to turn between the 1991 and 1994 conventions. During that time, some 30,000 Episcopalians in 1,100 congregations across the church participated in a parish dialogue about human sexuality which many said helped them to see gay and lesbian people--we’re still only at gay and lesbian, notice--as people rather than “an issue” As a result of this churchwide conversation, a “Statement of Koinonia” (fellowship) with gay and lesbian people drafted by our bishop at the time, John Shelby Spong, was signed by over 70 of his peers, including Bishop Sims, the same man who led the charge against ordination of openly gay and lesbian clergy! Sims said, “When I wrote that Pastoral Statement in 1977, I knew only one homosexual person up close. He scared me to death with his penetrating challenge that he was as complete a human being as I was.” He was talking about Louie Crew, the English professor who founded Integrity and later went on to serve on the Executive Council of the Episcopal Church. Today he lives not ten miles from this room and goes by Louie Clay, having taken the name of his husband Ernest of 40 years when they were legally married in 2013.

In 2003 the church made the news again when Gene Robinson, an out gay priest, was ordained the bishop of New Hampshire. He was not the first gay bishop: Otis Charles of Utah came out in 1993 while already seated, and Paul Moore of New York was posthumously outed by his daughter. But by choosing to consecrate him while already knowing that he is gay , the church again drew both criticism and praise from around the world.

As you probably know the Episcopal Church is part of a larger church, the Anglican Communion, which is somewhat symbolically overseen by the Archbishop of Canterbury in England. Some of the provinces of the church, notably Uganda and Nigeria, threatened to leave the communion as a result of Robinson’s consecration.

In response to this outcry, we in the Episcopal Church agreed somewhat reluctantly at the 2006 General Convention to "exercise restraint by not consenting to the consecration of any candidate to the episcopate whose manner of life presents a challenge to the wider church." Those of us who knew we presented the church with a challenge just by being in the room were strongly encouraged by Presiding Bishop Katharine Jefferts-Schori, and--in an unprecedented move--Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams to temporarily sacrifice ourselves in the name of unity. The Archbishop has no legislative authority outside the Church of England, but his presence and influence at that Convention was a sign of how close to coming apart he feared the Anglican Communion was.

However, we did not behave ourselves for long. In 2009, Mary Douglas Glasspool, an out lesbian, was ordained assistant bishop of Los Angeles. A significant number of congregations in the US and Canada then left their respective churches and created the Anglican Church in North America, an expression of conservative anglicanism which has not been formally recognized by the Communion. The foundations of the Episcopal church trembled again, but held.

Parishes and dioceses for many years performed home-grown rites for recognizing and blessing committed same-gender relationships, increasingly as civil marriage equality became the law of the land in more and more states beginning with Massachusetts in 2003. Finally, after numerous dioceses used a trial rite for blessing of a civil marriage for a number of years, General Convention in 2015 voted to make marriage equality available throughout the church, just days after the Supreme Court ruling, two years ago tomorrow, that brought marriage equality to every US state. There are still some dioceses and parishes which will not perform them but the practice has the official sanction of the church and in many congregations a wedding is a wedding, regardless of the genders of the couple..

That was a lot of information about the G and the L, now let’s talk briefly, I promise! about the B and the T, for bisexual and transgender. In 2012, the church finally began to recognize gender identity as another social justice issue that required prayerful work. The General Convention in that year resolved that being transgender was not in itself a barrier to ordination, and that the church must advocate for non-discrimination laws in the civil sector. In practice, transgender clergy have had a difficult time finding employment just as their sisters and brothers in the secular world struggle with job security. The poverty rate among the trans population is approximately four times that of the general populace.

Finally the B, where we have perhaps the most work to do. People who identify as bisexual make up the largest wedge of the LGBT pie, and yet are probably the least visible or understood. In 2014, a nonprofit organization called the Religious Institute published a workbook for people and congregations to begin increasing their literacy and creating welcome.

In the past ten years or so, a “Q” was sometimes added to LGBT, standing for queer. Once used mainly as an insult, the community has claimed and disarmed this word as an umbrella term for anyone whose combination of identity and attraction is not easily labeled. An increasing number of people, particularly young people, are resisting traditional norms and embracing a more fluid way of expressing themselves. If it wishes to remain relevant to them, the church needs to meet them where they are or at least hear their perspective.

In the meantime, all these lofty resolutions and decisions needed to be made real at home, in the parishes. In 2010, the Episcopal Church, by way of Integrity, joined 13 other denominations in the Believe Out Loud program which is intended to help congregations become more informed about issues of sexuality and gender and advocate more effectively for justice and equality.

Because LGBT inclusion came early to the Diocese of Newark, it has now somewhat faded from the forefront, and is perhaps even taken for granted by those who enjoy the benefits.,There were a few years when only a handful of us crossed the river to join the march, and response to the programs the OASIS offered has largely waned. This is not meant as an indictment of anyone. To some degree it means those early pioneers for justice succeeded in their work, and worthwhile issues like gun violence, the plight of the undocumented, refugees, hunger and housing insecurity all demand our attention as we seek to be Christ’s hands in a hurting world.

However, there is also overlap as race, culture and economic status bring a disparity in the degree to which our LGBT sisters and brothers enjoy welcome, safety and opportunity both in the church and the world. Paradoxically for those Christians who believe our faith calls us to seek justice for all God’s children, cultures which are heavily religious are often slower to offer acceptance.

Like the dire family apocalypse Jesus predicted in today’s gospel, some LGBT people find themselves abandoned or even betrayed by family and community when they need them most. Recently in Chechnya, over 100 gay men were recently rounded up by police, many turned in by relatives, and subjected to verbal and physical abuse. Around the world the disproportionate number of transgender women of color who die violently every year, their attackers rarely caught.

And right here at home, five of the 49 people who died in the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando last year were buried at the city’s expense, because their families, some of whom did not know the victims’ orientation or gender identity prior the attack, could not or would not plan their funerals. One father would not even claim his son’s body.

State legislatures, perhaps in a backlash to the Supreme Court ruling on marriage equality in 2015, have tried to enact new laws limiting protections and freedoms based on orientation or gender identity and expression. In over 50% of the states, being LGBT can still get you fired from your job. Sadly for people of faith, In many of these cases lawmakers cite “religious freedom” as grounds to perpetuate this discrimination. We as a population are more likely to fall victim to substance abuse and suicide, and our seniors, often without their own offspring to advocate for them, sometimes end up going back in the closet just to feel safe in retirement or nursing homes.

I realize that is a gloomy summation of where things are, but it serves to remind us that not everyone has found the love and safety we believe all God’s children deserve. There is plenty for which we can find joy as well. As I described, our own church has made tremendous strides to embrace LGBT people, as have a number of other mainline denominations. And earlier this month, the new Archbishop of Newark met a delegation of LGBT Catholics at Sacred Heart Basilica. There is much work to be done, but at least there has been dialogue.

In the wider world, out LGBT people are found in places of leadership in politics, the arts, business, and even professional sports. Schools, including the Bloomfield and Glen Ridge public districts, have gay-straight alliances and have adopted policies to ensure the fair treatment of transgender students. Our governor signed the first law in the country preventing parents from forcing conversion therapy on their kids. We find ourselves and our lives depicted increasingly in the media, sometimes even by actual LGBT people!

Here at Christ Church, a home was created for P-FLAG, an organization for the parents of LGBT children. Familiar symbols including the Believe Out Loud branding signal to passersby that this is a place where they are safe, welcomed, and celebrated. I am pleased that Christ Church has chosen to identify as a Believe Out Loud Episcopal Congregation and hope we can continue to explore together what that means in this time and place.

As Paul tells us today, in baptism, we all die to sin, just as Christ--who had no sin--died to sin, once for all. In our own tradition, we pledge at baptism to seek and serve Christ in all persons, loving them as ourselves, and respecting the dignity of every human being. Each of us has our own struggles with that, I suspect, as we encounter people who challenge the way we’ve come to understand our world. Those of us who are LGBT know we can cause those feelings simply by being who we are, but that doesn’t stop us from having them about other people either. If we agree that sin is anything that separates us from God, I ask we all be aware of those times when we allow the prejudices we all carry to win out over that calling to love each other without condition.

Thankfully, in perhaps the greatest news in today’s lessons, we have the best possible teacher. No matter how we might excel at loving one another, current science cannot calculate how small a fraction that is of the reckless, shameless love our God has for each of us. Every hair on our heads is counted, the secrets our hearts are open and all our dreams known.

My prayer today, for all of us, is that we never stop learning about one another, hearing one another’s stories, wiping one another’s tears, sharing one another’s joy, and seeking to recognize each person we meet as the precious creation of God that they are. That we turn to one another and say, “I see you, heterosexual newlyweds, homeless gay man, bisexual woman, transgender artist, queer youth. I see you, widowed priest, Choctaw bishop, black attorney, wheelchair warrior. I see you, undocumented worker, frightened asylum seeker, grieving mother, struggling breadwinner. I see you, proud soldier, neglected veteran, dedicated policewoman, devoted teacher, autistic child. And when I see you, I see Jesus.”

Then, and only then, will the church become what Bishop Browning proclaimed we were and thus challenged us to become: a church where all are truly welcome as their authentic selves, and there are truly no outcasts.

Then and only then will our baptismal covenant be truly realized.

Then and only then will the cries of those on the margins due to their attractions or their appearance or their circumstances be heard like God heard Hagar and her son and find comfort and peace within our walls.

Then and only then will “pride” not be code for “solidarity” in a struggle that never seems to end.

Then and only then will we not have to remind people that our lives matter because it will be safe to assume that they know and agree.

Then and only then will our laws truly bring liberty and justice to all.

Then and only then will we reveal the face of Christ, no longer bloody but GLORIOUS, upon the earth.

This year the Pride March will be televised for the first time, but I will not be marching today. After over twelve years of work among leaders of the movement, many of whom were coping by varying degrees, with the battle scars of their own history, I experienced burnout and had to step aside and into the wilderness. But I have not given up. I frequently pass this forlorn-looking old double-decker bus on a used car lot in Belleville, and--perhaps as a sign I’m becoming one of those Crazy Christians that Presiding Bishop Michael Curry says we should be-- I never fail to spend the next few miles daydreaming how cool it would be to ride down Fifth Avenue on that bus, decked out with a huge banner saying the Episcopal Diocese of Newark welcomes you… just as you are”. In my dream we use it not just for Pride but for Memorial Day, Thanksgiving, Martin Luther King Day, or any time where the church needs to make a visible witness to the world.

I ask God’s blessing upon you, and upon your own dreams. And If I figure out a way to get that bus, I’m saving you a seat. Amen.

SOURCES:

- "Making History, Twice at Grace Cathedral" by Louie (Crew) Clay, author's archives

- "A Statement of Koinonia" by the Rt. Rev. John Shelby Spong et al, Integrity archives

- "Father Refused to Claim Pulse Nightclub Shooting Victim" Orlando Latino 22 June 2016

- Bisexuality: Making Visible the Invisible in Faith Communities by the Rev. Marie Alford-Harkey and the Rev. Debra W. Haffner

- Adaptation from Everyone's Way of the Cross by Clarence Enzler

Monday, June 12, 2017

This is Not a Drill - Sermon for EfM Graduation

Trinity Sunday

I delivered the following sermon at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Teaneck, N.J., on Trinity Sunday (June 11, 2017) for the 2017 graduation ceremony from the Education for Ministry program, a four-year distance learning seminar on bible literacy, church history and theology for which I am co-mentor.

Through the written word and the spoken word, may we come to know Your living word. Amen.

I had that dream again recently, the one where you realize the end of the semester is coming and there’s a class you haven’t attended since the first week. You’re not even sure where it meets or what you did with the book, but there you are trying to find the classroom, late, hoping to beg the professor for mercy.

Psychologists, at least the ones on Google, say this dream is common and can represent latent anxiety about seemingly unrelated concerns. Some people who experience it report being in their pajamas or even naked, or wandering hallways that change before their eyes like an M.C. Escher drawing. In my particular version, there’s the added wrinkle of a dorm room that I paid for but haven’t been using, and on this fateful day I discovered my roommate had left it a disaster for which I was being held responsible. I woke up uneasy and confused, and trying to remember if any of it really happened.

I haven’t been a formal student in over five years so I have no idea what may have triggered it to recur. However, I told Margaret, one of three graduates from the Education for Ministry program whom we honor today, that if she finds a multiple-choice quiz on the Council of Nicea in her service leaflet today, she’s not dreaming and this is not a drill.

For the uninitiated, Education for Ministry (or EfM) is a four-year distance learning program to help adults explore their faith. It was born at and is managed by the University of the South, an Episcopal college and seminary in Sewanee, Tennessee. EfM graduates are typically not ordained, but the program reinforces the fact that all of us, clergy and laity alike, are called to engage in ministry, and their studies help them better recognize and employ their gifts to the glory of God and in service of others.

Today, as at every Sunday Eucharist, we heard readings from the gamut of scripture, beginning in the beginning, with the first of two stories of human creation in the Book of Genesis. This poetic account of how the world began does not, of course, reconcile with the things we are taught in science class. I assume most if not all of us have long accepted that the value of these ancient stories lies not in their provability, but in the narrative--as old as time--of a people and their God, who wrestle literally and figuratively with one another, break each other’s hearts, and find forgiveness.

This is all well and good when the stories are about talking serpents and burning bushes and people who live 700 years, but what happens when we get to Jesus? I think our culture has grown comfortable treating the “red letter” quotes in the Gospels as things he said verbatim, but one of the first things our second-year students learn is that the earliest of the Gospels was likely written at least sixty years after the events described. In our instant-replay world, our most direct experience of Jesus is subject to two generations of memory and interpretation. Additionally, in the Gospels as in the Hebrew scripture there are events--the resurrection and ascension being the most obvious among many--which just do not jive with what we observe and understand about the world around us.

The more you study, the louder this dissonance becomes. In our third-year text, Diarmaid MacCollough’s Christianity, the First 3,000 Years (which could be nicknamed 3,000 Years of Christians Behaving Badly) the historic and political origins of many of the doctrines most rank-and-file Christians take for granted are explored in depth. Some major decisions we might assume were made by the early disciples are in fact a lot more recent and seem to have been driven by political or practical concerns rather than the will of God. There are frequent occasions, right into our present century, when the institutional church hardly comes across as a hero. I re-read much of that book this year and it may well explain my anxious-exam dream. To quote Aristotle, Einstein or the British pop band UB40, depending on whom you ask, “The more I learn, the less I know.”

The more you study, the louder this dissonance becomes. In our third-year text, Diarmaid MacCollough’s Christianity, the First 3,000 Years (which could be nicknamed 3,000 Years of Christians Behaving Badly) the historic and political origins of many of the doctrines most rank-and-file Christians take for granted are explored in depth. Some major decisions we might assume were made by the early disciples are in fact a lot more recent and seem to have been driven by political or practical concerns rather than the will of God. There are frequent occasions, right into our present century, when the institutional church hardly comes across as a hero. I re-read much of that book this year and it may well explain my anxious-exam dream. To quote Aristotle, Einstein or the British pop band UB40, depending on whom you ask, “The more I learn, the less I know.”

What, then, does it mean when we say we believe? Are we forced to choose between donning intellectual blinders when we recite the creeds, or simply picking and choosing what we want to accept?

The Rev. Dr. Peter Savastano, who teaches religion and anthropology at Seton Hall, said in a sermon recently:

All of this lack of concrete historical evidence should not make our God a stranger to us. The God we experience in our lives--in the community of the church, in our compassion for one another, or in the beauty of creation--is everywhere, known as intimately to us as our own internal organs, and the love of that God is--as Anglican historian and Dean for Religious Studies at Stanford University, the Very Rev. Dr. Jane Shaw puts it--the “glue” of our relationships to one another. Although EfM is not therapy, we have seen real evidence of that glue as we supported one another through the changes and chances of life. In a recent reflection, Peter Grace, who graduated from the program in San Francisco in 2014, wrote “For us Christians, God is anything but unknowable: is not outside of us, but truly alive at the very center of our being and ‘does not live in shrines made by human hands.’ God is not a question to be answered, but a mystery to be embraced.”

Speaking of mysteries, today we focus on the Holy Trinity, the true nature of which theologians have been arguing about for almost as long as Christianity has been a thing. But this too need not and should not be limited to some arcane, eye-crossing concept that we blindly accept or mostly ignore. We are charged with using our gifts of memory, reason, and skill to explore what wise women and men of faith continue to say about this and how we can interpret it in our own lives. For example, the modern Franciscan Catholic theologian and author, Fr. Richard Rohr asserts, “In the beginning was the Relationship.” and goes on to simply and elegantly describe the three entities of the Trinity as “the God who made the world and everything in it,” “Jesus Christ, who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God” and “the spirit of truth...who abides with you and will be in you.”

The EfM journey may at times awaken cynicism, disenfranchisement, and uncertainty, but we would hardly be the first to wrestle with that. As we heard in today’s Gospel, even the disciples who saw Jesus in person experienced doubt. But there is great joy and comfort in exploring them together, and newfound ownership of a faith which one has examined carefully from many sides in an environment where such questions are not just welcomed, but expected.

Barbara, Margaret and Terry, it is the prayer of your EfM family that you proceed to the next chapter in your ministry equipped with clear-eyed wisdom about your faith and its often flawed but nonetheless inspiring history, having read the scriptures alongside expert--if sometimes slightly arid--context. You studied and practiced how to make the theological become personal; prayed, laughed, and sometimes wept with us.

We commission you today to use all these insights and experiences to build and strengthen the gifts you bring to a changing church and hurting world, to be--in the words of Teresa of Avila--the hands, the feet, the very body of Christ.

Finally, my sisters, farewell, but not goodbye. Your classmates and fellow alumni will be near at hand to continue supporting your walk of faith and service. We pray that the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of* the Holy Spirit be with you always, even to the end of the age. Amen.

I delivered the following sermon at St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Teaneck, N.J., on Trinity Sunday (June 11, 2017) for the 2017 graduation ceremony from the Education for Ministry program, a four-year distance learning seminar on bible literacy, church history and theology for which I am co-mentor.

Through the written word and the spoken word, may we come to know Your living word. Amen.

I had that dream again recently, the one where you realize the end of the semester is coming and there’s a class you haven’t attended since the first week. You’re not even sure where it meets or what you did with the book, but there you are trying to find the classroom, late, hoping to beg the professor for mercy.

Psychologists, at least the ones on Google, say this dream is common and can represent latent anxiety about seemingly unrelated concerns. Some people who experience it report being in their pajamas or even naked, or wandering hallways that change before their eyes like an M.C. Escher drawing. In my particular version, there’s the added wrinkle of a dorm room that I paid for but haven’t been using, and on this fateful day I discovered my roommate had left it a disaster for which I was being held responsible. I woke up uneasy and confused, and trying to remember if any of it really happened.

I haven’t been a formal student in over five years so I have no idea what may have triggered it to recur. However, I told Margaret, one of three graduates from the Education for Ministry program whom we honor today, that if she finds a multiple-choice quiz on the Council of Nicea in her service leaflet today, she’s not dreaming and this is not a drill.

For the uninitiated, Education for Ministry (or EfM) is a four-year distance learning program to help adults explore their faith. It was born at and is managed by the University of the South, an Episcopal college and seminary in Sewanee, Tennessee. EfM graduates are typically not ordained, but the program reinforces the fact that all of us, clergy and laity alike, are called to engage in ministry, and their studies help them better recognize and employ their gifts to the glory of God and in service of others.

Today, as at every Sunday Eucharist, we heard readings from the gamut of scripture, beginning in the beginning, with the first of two stories of human creation in the Book of Genesis. This poetic account of how the world began does not, of course, reconcile with the things we are taught in science class. I assume most if not all of us have long accepted that the value of these ancient stories lies not in their provability, but in the narrative--as old as time--of a people and their God, who wrestle literally and figuratively with one another, break each other’s hearts, and find forgiveness.

This is all well and good when the stories are about talking serpents and burning bushes and people who live 700 years, but what happens when we get to Jesus? I think our culture has grown comfortable treating the “red letter” quotes in the Gospels as things he said verbatim, but one of the first things our second-year students learn is that the earliest of the Gospels was likely written at least sixty years after the events described. In our instant-replay world, our most direct experience of Jesus is subject to two generations of memory and interpretation. Additionally, in the Gospels as in the Hebrew scripture there are events--the resurrection and ascension being the most obvious among many--which just do not jive with what we observe and understand about the world around us.

The more you study, the louder this dissonance becomes. In our third-year text, Diarmaid MacCollough’s Christianity, the First 3,000 Years (which could be nicknamed 3,000 Years of Christians Behaving Badly) the historic and political origins of many of the doctrines most rank-and-file Christians take for granted are explored in depth. Some major decisions we might assume were made by the early disciples are in fact a lot more recent and seem to have been driven by political or practical concerns rather than the will of God. There are frequent occasions, right into our present century, when the institutional church hardly comes across as a hero. I re-read much of that book this year and it may well explain my anxious-exam dream. To quote Aristotle, Einstein or the British pop band UB40, depending on whom you ask, “The more I learn, the less I know.”

The more you study, the louder this dissonance becomes. In our third-year text, Diarmaid MacCollough’s Christianity, the First 3,000 Years (which could be nicknamed 3,000 Years of Christians Behaving Badly) the historic and political origins of many of the doctrines most rank-and-file Christians take for granted are explored in depth. Some major decisions we might assume were made by the early disciples are in fact a lot more recent and seem to have been driven by political or practical concerns rather than the will of God. There are frequent occasions, right into our present century, when the institutional church hardly comes across as a hero. I re-read much of that book this year and it may well explain my anxious-exam dream. To quote Aristotle, Einstein or the British pop band UB40, depending on whom you ask, “The more I learn, the less I know.” What, then, does it mean when we say we believe? Are we forced to choose between donning intellectual blinders when we recite the creeds, or simply picking and choosing what we want to accept?

The Rev. Dr. Peter Savastano, who teaches religion and anthropology at Seton Hall, said in a sermon recently:

“In my own quest to understand the historical Jesus, the Bible, and the Jesus of theology, the scholars I have read repeatedly point out that we twenty-first century humans have lost the art of reading and interpreting scripture symbolically and allegorically. Influenced by scientism and rationalism, we prefer instead to read and interpret scripture as though it is a scientific text or a technical manual.In other words, in our endless quest for data, we run the risk of turning off our brains’ ability to find value in that which cannot be proven. Is it still possible to not know in the temporal understanding of that word, but nonetheless believe?

Conversely, in the world of the ancients and in the medieval world, scripture was interpreted allegorically and metaphorically, drawing on our human capacity for symbolic thinking, our intuitive faculties, and by the use of our creative imagination. To interpret a sacred story or a myth allegorically—and from an anthropological perspective the Bible is both —is to read and plumb its depths for truths and lessons that have universal import, truths that can only be revealed over time by the slow and painstaking process of meditation, prayer, and contemplation.

All of this lack of concrete historical evidence should not make our God a stranger to us. The God we experience in our lives--in the community of the church, in our compassion for one another, or in the beauty of creation--is everywhere, known as intimately to us as our own internal organs, and the love of that God is--as Anglican historian and Dean for Religious Studies at Stanford University, the Very Rev. Dr. Jane Shaw puts it--the “glue” of our relationships to one another. Although EfM is not therapy, we have seen real evidence of that glue as we supported one another through the changes and chances of life. In a recent reflection, Peter Grace, who graduated from the program in San Francisco in 2014, wrote “For us Christians, God is anything but unknowable: is not outside of us, but truly alive at the very center of our being and ‘does not live in shrines made by human hands.’ God is not a question to be answered, but a mystery to be embraced.”

Speaking of mysteries, today we focus on the Holy Trinity, the true nature of which theologians have been arguing about for almost as long as Christianity has been a thing. But this too need not and should not be limited to some arcane, eye-crossing concept that we blindly accept or mostly ignore. We are charged with using our gifts of memory, reason, and skill to explore what wise women and men of faith continue to say about this and how we can interpret it in our own lives. For example, the modern Franciscan Catholic theologian and author, Fr. Richard Rohr asserts, “In the beginning was the Relationship.” and goes on to simply and elegantly describe the three entities of the Trinity as “the God who made the world and everything in it,” “Jesus Christ, who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God” and “the spirit of truth...who abides with you and will be in you.”

The EfM journey may at times awaken cynicism, disenfranchisement, and uncertainty, but we would hardly be the first to wrestle with that. As we heard in today’s Gospel, even the disciples who saw Jesus in person experienced doubt. But there is great joy and comfort in exploring them together, and newfound ownership of a faith which one has examined carefully from many sides in an environment where such questions are not just welcomed, but expected.

Barbara, Margaret and Terry, it is the prayer of your EfM family that you proceed to the next chapter in your ministry equipped with clear-eyed wisdom about your faith and its often flawed but nonetheless inspiring history, having read the scriptures alongside expert--if sometimes slightly arid--context. You studied and practiced how to make the theological become personal; prayed, laughed, and sometimes wept with us.

We commission you today to use all these insights and experiences to build and strengthen the gifts you bring to a changing church and hurting world, to be--in the words of Teresa of Avila--the hands, the feet, the very body of Christ.

Finally, my sisters, farewell, but not goodbye. Your classmates and fellow alumni will be near at hand to continue supporting your walk of faith and service. We pray that the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of* the Holy Spirit be with you always, even to the end of the age. Amen.

Monday, May 29, 2017

Before Stonewall, there was Juliana: Historical Novel Explores LGBT Life During WW2

MEMORIAL DAY

It is easy to think of LGBT culture in New York as beginning with the Stonewall Riots of 1969. It is particularly easy for me, since I was also born that summer. Less, however, is known about what life was like for folks prior to that, which may well be because much of it took place in secret for the participants’ own safety: in unmarked clubs, with coded language that allowed communication under the noses of a population which would betray them to family, employers or the police. Being gay, or even something as innocent as a woman wearing pants in public, could cost you your job, home, and friendships, or get you arrested, raped, or beat up.

One of the prevailing themes for me is the degree to which LGBT people of this time period bought into the societal narrative that there was something wrong with them. Beyond entering into sham marriages and other means of protecting themselves, the characters continue to use words like “perversion” to talk about their own feelings. It is not hard to accept this as realistic given what they were hearing from the culture at large. Sadly this still occurs today despite all the “it gets better” cheerleading, positive role models and at least the patina of tolerance from official channels.

As we remember the sacrifices of those lost in our country’s wars, my mind goes particularly today to those who served and died for their country, likely leaving behind secret friends and partners who were not honored or comforted, and perhaps never even learned their fate.

It is easy to think of LGBT culture in New York as beginning with the Stonewall Riots of 1969. It is particularly easy for me, since I was also born that summer. Less, however, is known about what life was like for folks prior to that, which may well be because much of it took place in secret for the participants’ own safety: in unmarked clubs, with coded language that allowed communication under the noses of a population which would betray them to family, employers or the police. Being gay, or even something as innocent as a woman wearing pants in public, could cost you your job, home, and friendships, or get you arrested, raped, or beat up.

|

| Juliana cover. Used with author's permission. |

The first novel by playwright Vanda, Juliana gives us a look at this particular time and place by introducing her own characters to famous names of the day, many of whom risked their own careers, reputations, and marriages to indulge in “the love that dare not say its name” as the nation finds itself reluctantly drawn once again into war.

We see New York through the lens of a wide-eyed suburban Long Island girl “Al”, who moves to the city with her three childhood friends (Aggie, Danny, and Dickie). Each has dreams of making it big in the arts world, which they quickly discover is populated by folks quite unlike the ones they knew in Huntington. When big-talking producer Max Harlington III comes to their table, Aggie & Danny are entranced, while Al and Dickie remain skeptical. He takes them to clubs where cross-dressers, “bull daggers” and interracial couples all find sanctuary.

Taken in by the big promises of Max, the friends each set about fulfilling their dreams only to discover that, to quote Debbie Allen: ”Fame costs… and right here’s where you start payin’... in sweat.” Running between auditions, lessons, soul-killing day jobs, and infested apartments, they struggle to keep their friendships alive. It has always been assumed that the couples (Al and Danny, Aggie and Dickie) would marry someday, but as the book progresses, that dream becomes as elusive as the thought of your name up in lights.

For Al, the biggest distraction is Juliana, a talented vocal performer who seems perpetually on the brink of success. Juliana awakens feelings in Al she was unaware she possessed, then shocks her further by making it clear the interest is mutual. Although Al continues to harbor some disdain for Max, he proves useful in making this connection. When things with Juliana go awry, however, Al flees back to Max’s place only to make a further unwelcome discovery that throws all her plans for the future into disarray.

|

| Vanda Used with author's permission. |

The declaration of war in 1941 sends the characters’ lives in different directions. Max, Dickie, and Danny all end up overseas and Al contributes much of her time and energy to the Stage Door Canteen, a real-life place on 44th Street where military men were fed and entertained by Broadway personalities. Here she mingles with greats like Katharine Hepburn, Ethel Merman, Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne, who performed or helped staff the club. Many of these stars had cameos in a film named for the club, which stood on the site of the former New York Times printing press.

Dickie, Max and Danny all make it home alive, but not unscarred. They describe the conditions gay men and women encountered during deployment… perhaps the roots of “don’t ask, don’t tell” where camp behavior was tolerated and even encouraged in some quarters, but one misplaced word of affection could erase years of dedicated service with the stroke of a pen. Small wonder that a study 60 years later found almost 15% of closeted LGBT veterans attempt suicide: imagine the nightmarish memories of combat layered with the constant fear of being found out.

Meanwhile, Al--at a breaking point--confides in best friend Aggie, whom she has helped through some serious setbacks, only to discover that their bond is not stronger than the prejudices with which they were all raised. Betrayed, Al turns again to the unconventional people from whom she continues to try to distinguish herself. I found it interesting and even a little vexing that these individuals, apparently further along the road of self-acceptance, continue to tolerate this behavior almost without reproach. It is not always clear what she brings to the table of these friendships besides judginess and a need for a whole lot of hand-holding. But I suspect then, as now, there are those who see their younger selves in the newcomer and thus deal with such foibles gracefully.

Nevertheless they take her under their wing and we see such real-life scenes of early gay New York as Spivey’s Roof, a nightclub on the Upper East Side where gay men and women were allowed to congregate as long as they (mostly) behaved. A young Walter Liberace played here briefly before unwittingly crossing Madame Spivy, the club’s imperious owner, namesake, and star performer, a scene described in the book.

The first volume leaves off with relationships on hold and a lot of unanswered questions. Luckily, a sequel which picks up at around D-Day is due out this summer. Meantime, an ensemble cast periodically performs scenes from the book at the legendary Duplex nightclub on Christopher Street, just steps from the Stonewall Tavern. You can learn about upcoming events on the Juliana Project Facebook page or by visiting vandawriter.com and subscribing to her free newsletter.

As we remember the sacrifices of those lost in our country’s wars, my mind goes particularly today to those who served and died for their country, likely leaving behind secret friends and partners who were not honored or comforted, and perhaps never even learned their fate.